A fast Wordfeud Solver in Rust

A few years ago I became intrigued by the Rust programming language. Like many other people I enjoy playing the popular Wordfeud game. I was looking for a programming project to exercise my Rust skills, and creating a wordfeud solver in Rust seemed like a nice challenge!

This article explains the algorithm used, how I implemented it in Rust, and how it performs. Along the way I explain some of the design choices made.

The Wordfeud game

The Wordfeud game is derived from Scrabble. The objective of the game is to put words on the 15x15 game board with the letter tiles you have. You score points based on the value of each tile, and the type of the square where the tile is placed. In addition to the regular tiles you can also get a blank tile that can be assigned any letter when put on the board, but has a value of 0 points.

Wordfeud can be played in different languages (English, German, French, Spanish, Dutch, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Portuguese and Finnish). Each language has a different tile distribution. The details of the game are explained here.

A Wordfeud Solver

The initial goal for my Wordfeud Solver was to create a Rust library that can be used to build a Wordfeud player.

- Read a wordlist for the selected language

- Given the state of the game board and a set of tiles, calculate all possible words that can be played

- Calculate the scores for all words and return the top scores

Wordfeud Solver algorithm

The solver presented here is based on the excellent wordfeudplayer Python package.

The wordlist

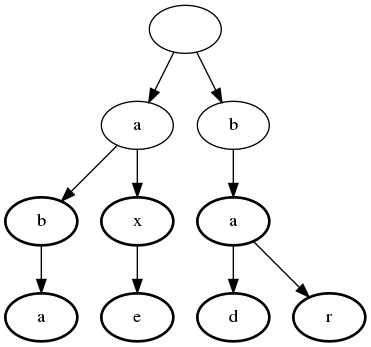

The wordlist is stored in a trie data structure. A trie is a search tree where each node has an associated label. All the descendants of a node have a common prefix. The root node is the empty string.

This example stores the words ab, aba, ax, axe, ba, bar, bad:

The bold nodes are terminal, which means they represent a valid word. Non-terminal nodes represent a valid prefix.

The board

The wordfeud board can be thought of as a square grid of 15x15 cells, where each cell can be empty or contain a tile. It can be represented by 15 lines of 15 characters. Lower case letters are normal tiles, while upper case letters represent a blank tile used as a wildcard. For example, the screenshot above shows like this:

...............

...............

............z..

............if.

.........dental

..........v.ex.

.......h..e....

......hedonIc..

....r..d..l....

....o..o..y....

....brent......

....o..i..v....

.gaits.S..e....

....i..munged..

....c.....a....

Find all possible words

The steps to calculate all words that can be played with our letters will be in pseudo code:

for direction in horizontal, vertical {

for row in rows[direction] {

find possible word start positions in row

for pos in start positions {

find all words starting at pos

}

}

}Find start positions in row

A valid word must be connected, which means that it must “touch” a word in the other direction.

Connected positions are empty cells that are horizontally or vertically adjacent to on occupied cell.

For the above example, the connected cells for the horizontal direction are indicated by a * below (each cell with a tile is also connected):

...............

............*..

............z*.

.........***if*

.........dental

.......*.*v*ex*

......*h**e***.

....*.hedonIc..

....r.*d**l**..

....o**o*.y....

....brent.*....

.***o**i*.v....

.gaits.S**e**..

.***i*.munged..

....c..***a**..

A word can start in a position if we have enough letters to build a word to the next connected position.

But a word can not start in a cell next to an occupied cell (because in that case the occupied cell would be part of the word).

The possible start positions with 7 letters for the example are indicated with a + here:

...............

......+++++++..

.....+++++++z..

...+++++++++if.

..+++++++dental

.+++++++++v.ex.

+++++++h.+e.++.

++++++hedonIc..

++++r.+d.+l.+..

++++o.+o.+y....

++++brent.+....

++++o.+i.+v....

+gaits.S.+e.+..

++++i.+munged..

++++c.++++a.+..

Find possible letters for each position

Before we start building words we need to find the possible letters that can go at each position in a row.

If a cell is empty and not connected each letter from the wordlist is possible.

If a cell is occupied that letter is fixed.

If a cell is empty and connected only letters that make valid connecting words can go there.

For example, in the first connected position below the possible letters are: a, e, i, d, forming words ad, ed, id, od with the d in the second line.

.........***if*

.........dental

Building words

For each start position we find the words that can start at that position.

As input we have:

- the

wordlist - the current

nodein the wordlist - the

row: a list of 15 cells - the

rowdata: set of letters, and connected status for each cell in the row - the

positionto start from - the

letterswe can use

We generate the words in a recursive fashion, starting at the root of the wordlist, with an empty word.

If the current position has a tile, and the tile is a child of the current node, add it to the word, and recursively yield from the next position.

If the current position is empty, yield the current word if it is valid (length > 1 and connected).

Then try to use each of our remaining letters:

- for a blank, continue with each child of the current

nodethat is a valid letter for thisposition. - for a normal tile, continue with this letter if it is valid for this

position.

At each recursive step, a used letter is removed from letters, and added to word, the position is incremented, and at the same time we descend in the wordlist.

Wordfeud Solver in Rust

Rust promises the ability to make software both fast, memory-efficient, and reliable. With that in mind, I started to port the Python version to Rust.

Data types

The static type system in Rust can help to prevent programming errors. As an example, in the wordfeud solver we can distinguish several types that are similar but have different roles and operations:

- A tile on the board

- A tile in the rack

- A grid cell on the board that is empty or contains a tile

My first attempt used char to represent a tile, and Vec<char> or String to represent words, similar to the Python wordfeud player.

An * is used for a blank tile, and an uppercase letter is an assigned blank on the board.

Basic data types

Instead I decided to use a newtype wrapper around a u8, for a couple of reasons:

- It takes only 1 byte to store, allowing a space efficient wordlist

- All the Wordfeud tile distributions have less than 32 different tiles, so I can use a

u32to encode a set of letters - The Spanish tileset has a number of 2 letter tiles (

CH,LL,RR)

/// Code 1..31 for valid letter in wordlist (a..z plus language specific)

pub type Label = u8;

/// Tile code used to represent `Tile` or `Letter`. See [`Codec`](crate::Codec).

pub type Code = u8;

I reserved 0 to represent an empty cell, and codes 1..31 for tile labels. By using a NonZeroU8 a cell can be stored as a Option

/// Either a regular letter or a `blank` ("*") that can be used as any letter.

pub struct Letter(pub(super) NonZeroU8);

/// A tile on the board, either a regular letter or a wildcard (blank used as letter)

pub struct Tile(pub(super) NonZeroU8);

/// A cell on the board that is either empty or contains a tile

pub struct Cell(pub(super) Option<Tile>);

Access to the inner value is restricted to the tiles module, to ensure that only valid values can be stored in a type.

A trait Item defines common operations for the above types.

TryFrom<Code ... >says anItemcan be made from aCode, but it may failInto<Code>: conversion fromItemtoCodeis infallible

/// common trait for Tile, Letter, Cell

pub trait Item:

Debug + Clone + Copy + PartialEq + Default + Into<Code> + TryFrom<Code, Error = Error>

{

fn code(&self) -> Code;

}

Collections

A List trait defines common operations on a list of Item.

/// common trait for a list of `Item`

pub trait List:

Debug + Default + Clone + Copy + Index<usize> + IndexMut<usize> + Index<Range<usize>> + PartialEq

{

type Item;

fn len(&self) -> usize;

fn is_empty(&self) -> bool;

fn push(&mut self, item: Self::Item);

fn iter(&self) -> Iter<Self::Item>;

}

pub(super) type Items<T> = ArrayVec<[T; DIM]>;

I used the tinyvec ArrayVec to store Items. The maximum size is 16 items.

An ArrayVec is similar to Vec but it is backed by a fixed size array. That means no heap allocations are used, and it is cheap to copy.

With the types introduced above we can use an ItemList<Tile> for a word on the board, an ItemList<Cell> for a row of cells on the board, and an ItemList<Letter> for a bunch of letters to play.

/// A collection of Tile

pub type Word = ItemList<Tile>;

/// A collection of Cell

pub type Row = ItemList<Cell>;

/// A collection of Letter

pub type Letters = ItemList<Letter>;

Conversion to / from string

A Codec struct is used to translate between textual representation and tile codes.

// String corresponding to tile code

pub type Token = String;

/// A list of `Token`'s

pub type Tokens = Vec<Token>;

struct CodeSet {

encoder: HashMap<String, Code>,

decoder: Vec<[Option<char>; 2]>,

}

/// Translate from string to label codes and vice versa.

/// Each wordfeud tile is translated to a code.

/// - 0: No tile (empty square)

/// - 1 .. 26: `a` .. `z`

/// - 27 .. 31: Non-ascii tiles, depending on codec

/// - 64: Blank tile `*` (unassigned)

/// - 65 .. 90: `A` .. `Z` (blank tile assigned to `a`..`z`)

/// - 91 .. 95: Blank tile assigned, depending on codec

///

pub struct Codec {

codeset: CodeSet,

}

impl Codec {

fn tokenize(&self, word: &str) -> Tokens { ... }

pub fn encode(&self, word: &str) -> Result<Vec<u8>, Error> { ... }

pub fn decode(&self, codes: &[Code]) -> Vec<String> { ... }

}

The Wordlist in Rust

The wordlist is one of the central data structures in wordfeud-solver.

Finding all possible words from a given start position is done in the Wordlist::matches method.

A time and space efficient data structure is crucial to the performance of the solver. As a typical example, the dutch wordlist has 340.674 words, and the wordlist tree has 990.506 nodes. From each node you can navigate to all the child nodes. There can be 0..32 child nodes.

I investigated several alternatives.

- A hashmap:

HashMap<Letter,Node> - An array of child nodes:

[Option<Box<Node>; NLETTERS] - Using trie_rs: a memory efficient trie library based on LOUDS

- A custom trie data structure where each node stores a

(u32, LabelSet)tuple, au8label and aboolterminal

I did a simple benchmark to compare the speed for a matches operation and the memory used when reading the dutch wordlist mentioned earlier.

| Method | benchmark time (usec) | memory usage (MB) | peak memory usage (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hashmap | 3.0 | 213 | 213 |

| [Option<Box |

2.0 | 210 | 210 |

| trie_rs | ? | 4.1 | 71.6 |

| custom trie | 1.1 | 10.0 | 95.5 |

The memory usage for the last two methods shows two phases: in the first phase the trie is build using a naive trie, in the second phase the trie is converted to a memory efficient representation.

I can’t reproduce the benchmark time for the trie_rs method, but it is slower than the others.

The custom trie I settled upon is memory efficient: it requires ~ 10 byte per node. It is also the fastest.

All the nodes are stored in a single Vec<(u32, LabelSet)>. The nodes are stored in “breadth first” order.

For each node, the u32 is the index in nodes vec of the first child node. The LabelSet is a bitset indicating which children are present in the node. To find a specific child label we find the index of the label in the labelset, and add the index of the first child.

The labels for the nodes are stored in a separate Vec<Label>. A Vec<bool> stores the terminal property for each node.

We can take advantage of the separate build phase by serializing the final wordlist and storing it on disk. The next time we need it we can just read the serialized wordlist from disk without having to build it. That saves substantial time and memory.

/// A bitset representing labels present in a `wordlist` node

pub struct LabelSet(u32);

/// A trie data structure that holds all the possible words.

pub struct Wordlist {

/// List of nodes in trie. Each node is a tuple with the index of the first

/// child node, and a `CharSet` with the labels of all child nodes.

pub nodes: Vec<(u32, LabelSet)>,

/// List of labels.

pub labels: Vec<Label>,

/// List indicating terminal nodes

pub terminal: Vec<bool>,

/// Path of the wordfile used to build the wordlist.

/// Empty if the wordlist is not build from a file.

pub wordfile: String,

/// The set of all characters used in the wordlist.

pub all_labels: LabelSet,

/// The number of words in the wordlist

pub word_count: usize,

/// The number of nodes in the wordlist.

pub node_count: usize,

/// Encode words to/from labelvec

pub codec: Codec,

}

Wordlist Matches

The Python wordfeud player has a recursive Node::matches method that is a generator function.

Using a recursive generator results in an elegant and compact implementation.

I show it here without further explanation, that would take us too far.

# The original Python version of Node::matches:

class Node(object):

def matches(self, row, rowdata, pos, letters, variant, word='', connecting=False, extending=False):

if pos < len(row) and (variant & self.variants) != 0:

if row[pos] != ' ':

child = self.children.get(row[pos].lower())

if child:

yield from child.matches(row, rowdata, pos+1, letters, variant, word+row[pos], True, extending)

else:

if self.word and connecting and extending and len(word) > 1:

yield word

if pos < len(row)-1:

valid_chars, connected = rowdata[pos]

for i, ch in enumerate(letters):

if not ch in valid_chars and ch != '*':

continue

if letters.find(ch, 0, i) != -1:

continue

if ch == '*':

# wildcard

next_letters = letters[:i] + letters[i+1:]

for wc, child in self.children.items():

if wc in valid_chars:

yield from child.matches(row, rowdata, pos+1, next_letters, variant, word+wc.upper(), connecting or connected, True)

child = self.children.get(ch)

if child:

yield from child.matches(row, rowdata, pos+1, letters[:i] + letters[i+1:], variant, word+ch, connecting or connected, True)

Unfortunately, Rust does not (yet) support generators, so porting this to Rust was a hurdle on the way.

My first attempt was to return a Vec<Word> instead. Each invocation of matches begins with allocating an empty Vec, that is extended recursively and finally returned. It is relatively simple and it works. But it means a lot of temporary allocations are done, which is bad for performance.

By writing a custom recursive iterator that maintains the necessary state I could get rid of the temporary allocations, at the cost of some extra complexity.

The Matches struct stores a reference to the Wordlist and the static Row and RowData arguments.

The child_iter deque holds the variable state when recursively iterating the wordlist. Descending the tree pushes new arguments to the end of the deque, and iteration pops from the front.

pub struct Matches<'a> {

wordlist: &'a Wordlist,

row: Row,

rowdata: &'a RowData,

child_iter: VecDeque<Args>,

}

impl<'a> Iterator for Matches<'a> {

type Item = Word;

fn next(&mut self) -> Option<Self::Item> {

while let Some(mut args) = self.child_iter.pop_front() {

if ... {

...

self.child_iter.push_back(Args { ... })

}

...

if ... {

return Some(args.word);

}

}

None

}

}

impl Wordlist {

/// Return a list of matching words.

pub fn matches<'a>(

&'a self,

node: usize,

row: Row,

rowdata: &'a RowData,

pos: usize,

letters: &Letters,

) -> Matches {

let args = Args {

node,

pos,

letters: *letters,

word: Word::new(),

next: None,

connecting: false,

extending: false,

};

Matches::new(self, row, rowdata, args)

}

}

The start_indices method returns the possible indices in a row where a word can start:

/// Returns the indices in `row` where a word can start, given the connection data in `rowdata`.

/// `maxdist` is the maximum distance for connecting, typically the number of letters we have.

pub fn start_indices(&self, row: Row, rowdata: &RowData, maxdist: usize)

-> Vec<usize>;

Iterating over the start indices results in an iterator for all the words in a row.

pub fn words<'a>(

&'a self,

row: &'a Row,

rowdata: &'a RowData,

letters: &'a Letters,

maxdist: Option<usize>,

) -> impl Iterator<Item = (usize, Word)> + 'a {

let mut row = *row;

row.push(Cell::EMPTY); // extend row with an empty square

let maxdist = maxdist.unwrap_or_else(|| letters.len());

let indices = self.start_indices(row, rowdata, maxdist);

indices.into_iter().flat_map(move |pos| {

self.matches(0, row, rowdata, pos, &letters)

.map(move |word| (pos, word))

})

}

The Board in Rust

The wordfeud_solver should support different languages and wordlists.

The Language enum specifies the supported languages. Currently, English, Dutch and Swedish are supported, but more will be added in the future.

For each language there is a TileSet that specifies the tile distribution for that language, and the Codec to translate between words/letters and tile codes.

/// These languages are supported.

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

pub enum Language {

/// English

EN,

/// Dutch

NL,

/// Swedish

SE,

}

/// A tileset for `wordfeud`. It contains the tile distribution for a supported language,

/// and a codec to translate between words and tiles. The tile distributions are specified on the

/// [Wordfeud.com website](https://wordfeud.com/wf/help/)

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

pub struct TileSet<'a> {

pub language: Language,

pub tiles: &'a [TileInfo],

codec: Codec,

}

The Board struct represents the state of the Wordfeud board. It consists of:

- The

boarditself: a 15x15 grid with word and letter bonus cells - The

horizontalandverticalstate: tiles played on the board in horizontal and vertical direction. Note thatverticalis simply the transposed version ofhorizontal - The

rowdata: the possible letters and connected state, for each horizontal and vertical row. Since this depends only on the boardhorizontalandverticalstate it is precalculated when the state changes - The

tileset - The

wordlist

/// A set of letters

pub type LetterSet = LabelSet;

/// The dimension of wordfeud board: N x N squares

pub const N: usize = 15;

type RowCache = [(LetterSet, bool); N + 1];

/// A list of 0..N (possible letters, connected) tuples.

pub type RowData = ArrayVec<RowCache>;

type State = [Row; N];

/// Represents the state of a `wordfeud` board.

/// * A grid of 15x15 squares with possible letter/word bonus,

/// * The tile distribution for language used (number of letters, and value of each letter),

/// * The wordlist used for the game.

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

pub struct Board<'a> {

board: Grid,

empty_row: Row,

horizontal: State,

vertical: State,

rowdata: [[RowData; N]; 2],

tileset: TileSet<'a>,

wordlist: Wordlist,

}

With all the above in place getting all the words for a row on the board is simple:

impl Board {

// ....

/// Returns a list with (`pos`, `word`) tuples for all words that can be played on `row`

/// with index `i`, in direction `horizontal`, given `letters`.

/// In the returned tuples, `pos` is the start index of the `word` in `row`.

pub fn words(

&self,

row: &Row,

horizontal: bool,

i: usize,

letters: Letters,

) -> Vec<(usize, Word)> {

let rowdata = self.rowdata[horizontal as usize][i];

self.wordlist

.words(&row, &rowdata, &letters, None)

.collect()

}

And finally all word scores are calculated:

- collect the words for all horizontal and vertical rows

- calculate the score for each word

/// Calculate the score for each word that can be played on the board with `letters`.

/// Return a list of (`x`, `y`, `horizontal`, `word`, `score`) tuples.

/// ## Examples

/// ```

/// # use wordfeud_solver::{Board, Error};

/// let board = Board::default().with_wordlist_from_words(&["the", "quick", "brown", "fox"])?;

/// let res = board.calc_all_word_scores("befnrowx")?;

/// assert_eq!(res.len(),16);

/// # Ok::<(), Error>(())

/// ```

/// In this example 16 results are returned: 8 in horizontal and 8 in vertical direction.

/// See also [`Board::words`](Board::words).

pub fn calc_all_word_scores<T: TryIntoLetters>(&self, letters: T) -> Result<Vec<Score>, Error> {

let letters = letters.try_into_letters(&self.codec())?;

self.calc_all_word_scores_inner(letters)

}

fn calc_all_word_scores_inner(&self, letters: Letters) -> Result<Vec<Score>, Error> {

let mut scores: Vec<Score> = Vec::new();

let hor_scores = |(i, row)| {

let words = self.words(row, true, i, letters);

let mut scores: Vec<Score> = Vec::new();

for (x, word) in words {

let points = self.calc_word_points_unchecked(&word, x, i, true, true);

scores.push(Score {

x,

y: i,

horizontal: true,

word,

score: points,

});

}

scores

};

let ver_scores = |(i, row)| {

let words = self.words(row, false, i, letters);

let mut scores: Vec<Score> = Vec::new();

for (y, word) in words {

let points = self.calc_word_points_unchecked(&word, i, y, false, true);

scores.push(Score {

x: i,

y,

horizontal: false,

word,

score: points,

});

}

scores

};

{

scores.extend(self.horizontal.iter().enumerate().map(hor_scores).flatten());

scores.extend(self.vertical.iter().enumerate().map(ver_scores).flatten());

}

Ok(scores)

}

}

Performance

Here are the results of a simple benchmark test: read a (dutch) wordlist, and calculate all the word scores for a test board. The first case with 7 letters (no blanks), the second with 6 letters and 1 blank. The test is run on an Asus Zenbook with an Intel Core-i5 (8th gen). It shows that the best Rust version is more than 100 times faster than the Python version, and more than 8 times faster than the initial Rust version.

| normal letters | one blank | read wordlist | remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Python wordfeud player | 34 ms | 144 ms | 3.73 s | |

| wordfeud_solver initial | 2.2 ms | 8.0 ms | 273 ms | |

| wordfeud_solver 0.3.2 | 0.55 ms | 2.5 ms | 590 ms | wordlist text |

| wordfeud_solver 0.3.2 | 0.37 ms | 1.9 ms | 47 ms | wordlist bincoded |

| wordfeud_solver rayon | 0.37 ms | 1.3 ms | 590 ms | wordlist text |

| wordfeud_solver rayon | 0.26 ms | 0.9 ms | 44 ms | wordlist bincoded |

NOTE: I can’t explain why calculating the word scores becomes faster when the wordlist is read from a bincoded file, but it is reproducible.

Using Rayon for parallel computing

I experimented with rayon to calculate scores in parallel. On my quad core i5 it results in a speed-up of 1.4x with normal letters, and 2.1x with a single blank. This is a significant improvement, but less than the maximum speed-up of 4x you would expect with 4 cores.

Conclusions

I really enjoyed embarking on this project, and I learned a lot from it. I have done a lot of Python and C programming in the past, so I can make a comparison.

Rust vs Python

Rust is a good language for systems programming, while Python is more suitable for rapid development and scripting. In my experience Python is elegant and readable, and I feel a lot more productive using Python. The huge amount of high quality libraries, not having to wait for a compiler, the ease of interactive environments like Jupyter notebook attribute a lot. On the other hand, when performance and robustness is important, Rust is a big winner! Its unique ownership model makes safe concurrent programming possible, which can result in big performance gains. You can do parallel processing in Python, but because of the “GIL” (Global Interpreter Lock) multiple threads can not run at the same time. The solution is typically to run multiple processes in parallel, which requires additional overhead for communication.

Rust vs C

Compared to C, Rust feels much more high level and expressive, with functional programming features like iterators and combinators, automatic type inference, traits and generics. The learning curve is steep, but I feel it pays off. Cargo makes it very easy to set up, build and distribute a project.

What is next?

Make it smarter

So now we can calculate the highest scores very fast. But in Wordfeud, the highest score is usually not the best! By playing a word you may enable your opponent to score a high word or letter bonus. So when you look for the best move you have to consider the possible responses from your opponent.

In a next article I want to show how the wordfeud-solver library can be used to find the “best” sccore by evaluating possible counter moves.

Read a Wordfeud board

I will also show how you use image processing and pattern matching to “read” the board state from a Wordfeud game screenshot.

Finally

If you made it this far, I hope you enjoyed reading this article!